Press Releases & Articles

When gondola storage becomes an art gallery

“ALL THAT IS WILD IS GOOD AND FREE”

THE GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK PHOTOGRAPHY OF ALEXANDER LINDSAY

2019

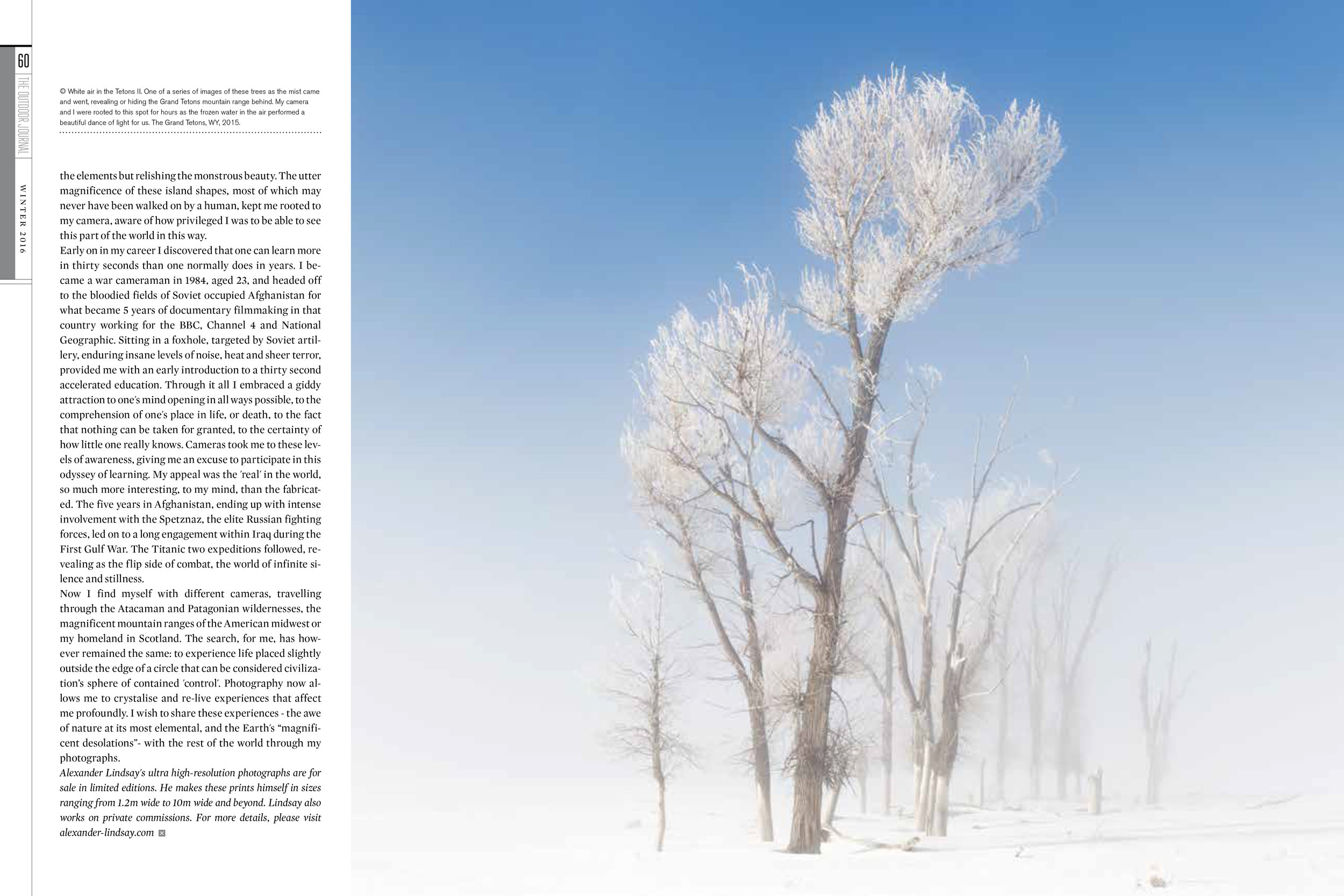

Alexander Lindsay’s photographs are expansive, both in their theme and in their scale.

So much so that most conventional art galleries don’t have the wall space for a show. It was serendipitous, then, when Lindsay met Jay and Connie Kemmerer, owners of Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, who pitched the idea of transforming the Bridger Gondola storage facility into a temporary art gallery to house Lindsay’s images.

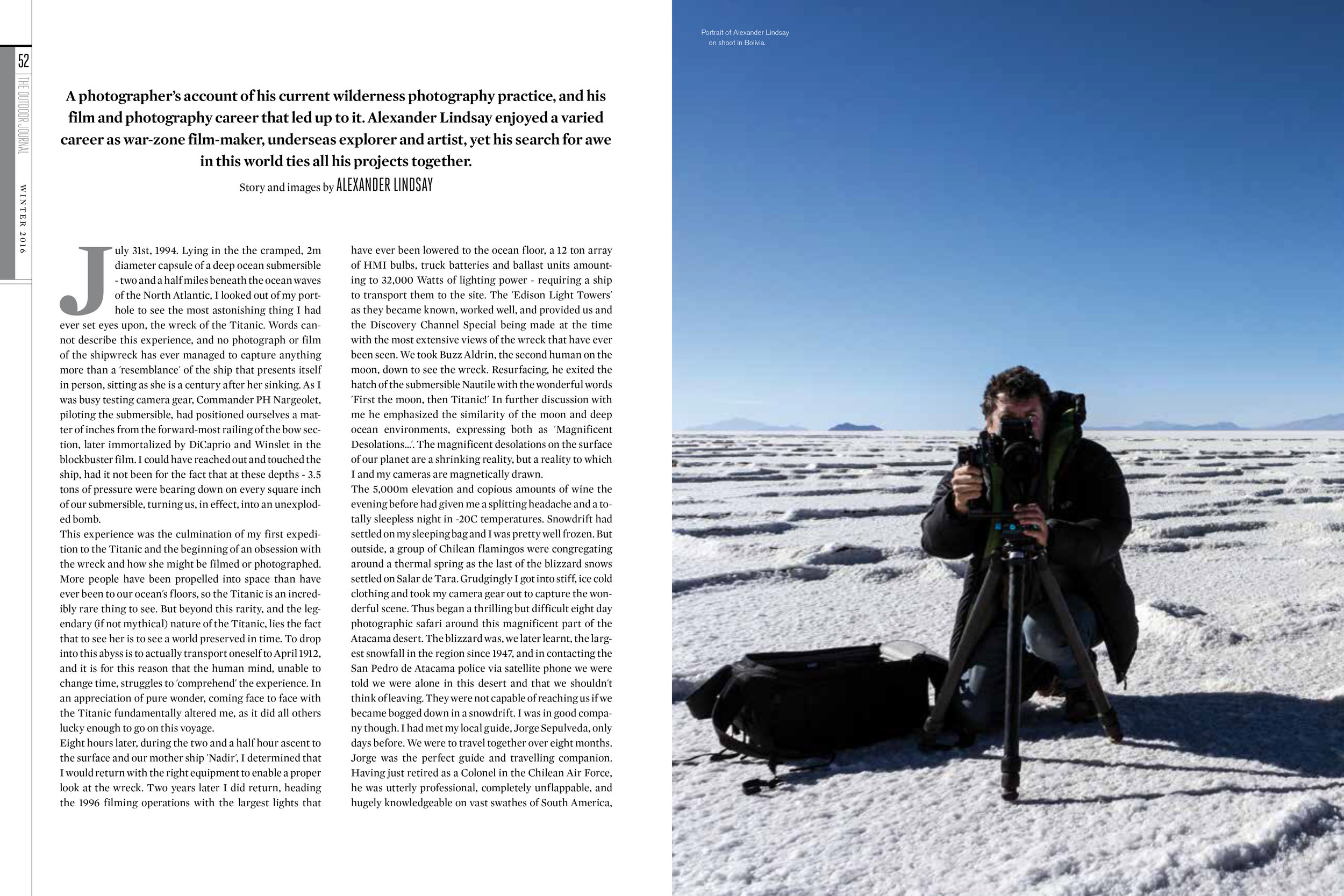

The Scottish-English photographer first came to the Tetons in 2015 on a private commission and spent the months of January and September immersed in the project. He split his between photographing the park and developing prints in the studio.

Most of the time he found himself working alone or accompanied by a single nature guide. Lindsay found that time in nature and with the photographic process to be an incredibly contemplative one.

“There is a beauty of being totally alone,” he said. “I view it as a meditative process. And, of course, it’s art, it’s creation, but it is also a meditation with nature. I like the deliberate slowness of it. I like the sheer effort of it in every aspect.”

The show at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort is the first time Lindsay’s Grand Teton National Park images are being exhibited in the United States. The industrial space gives his prints, which range in width from 40 inches to 20 feet, room to breathe.

The space received a makeover of sorts for the show, with new lighting installed. The prints will be mounted on aluminum sheets and suspended by steel cables. While the show is up the gondolas cannot to be stored in their usual home, which is why the exhibition will have a relatively short one-week run.

“You know, it’s not an art gallery,” Lindsay said. “But I think it’s going to look fantastic, actually. The pictures and the way they are presented are really pristine and clean and sort of minimalist, and then you’re in this kind of crazy industrial space.”

Before completing his photography series of the Tetons, Lindsay worked on a series of more extreme projects, like being a documentary film producer in war zones and making expeditions to the Titanic shipwreck order to photograph it.

Early in his life Lindsay wanted to be an engineer. It was the technical prowess of digital cameras that first attracted him to the art form. His ability to bring out his landscapes and photo subjects in sharp detail immediately catches the eye.

“That got me into digital photography — the ability of digital photographs to stitch together to create truly, incredibly detailed images,” Lindsay said. “I just decided I wanted to do it. It was just a new chapter for me.”

The first project was an eight-month, 25,000-mile journey in 2013 that began in the Atacama Desert of Northern Chile and led him throughout the South American continent, crossing the Bolivian Salt Flats, and the rainforests of Central Chile, as well as Patagonia and Cape Horn.

“It’s led from one project to another,” Lindsay said.

But at the core of his work is the desire to remain true to nature and to document it faithfully and reverently.

“Even though it’s an art form, it’s very much it’s very much a documentary art form,” Lindsay said. “The wonder really is the wonder of nature.”

The show runs Thursday through Tuesday. Lindsay will be available for private tours of the exhibition.

© Leonor

in search of wonder

THE OUTDOOR JOURNAl - Story and images by ALEXANDER LINDSAY

2016

ALTITUDE - THE PHOTOGRAPHY OF ALEXANDER LINDSAY

by Patrick Mark

2015

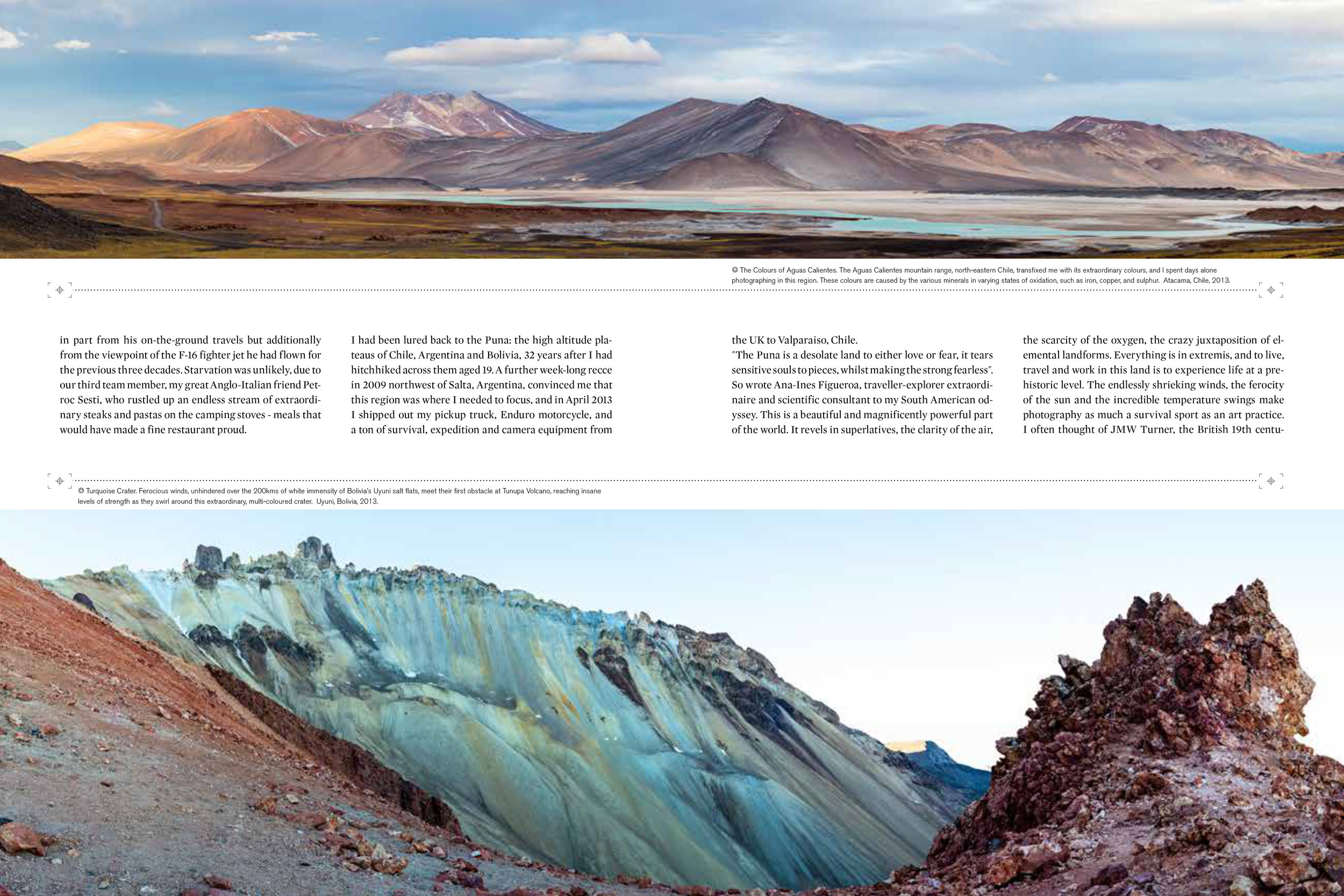

Forty feet wide, a gargantuan photographic print is at first unsettling. The image demands attention. It has a sense of finality – and an insistent, pulsating, presence. Approach closer and a journey begins, the eye wandering through desolate valleys and angry skies. Closer still and sharp, tangible details emerge: the seams of copper, iron and sulphur on distant volcanoes, individual flamingos in salt lakes five kilometres away.

The monumental prints in Alexander Lindsay’s ALTITUDE series are the latest expressions of his life’s journey as photographer, filmmaker and artist. His past work (including award-winning films) has ranged across ancient cycles of life and death, epic battlefields and vast expanses of ocean. Up close, Lindsay’s imagery has been consistently compelling. Afghan Mujahidin combat footage of outstanding rawness and power; aerial scenes of Russian Special Forces wreaking vengeance in the Panshir Valley; the heaving seas captured from a 12th century Scottish long-ship; and the looming hulk of the Titanic, four kilometres deep in the North Atlantic abyss.

Diverse subjects perhaps, but for Lindsay they share a common link: ‘My fascination lies in peering over the edges of the unknown… Certainly the combat situations, looking at and even entering the wreck of the Titanic and travelling and capturing these extraordinary regions of the world, all induce in me an identical sensation that I find incredibly hard to describe in words.’

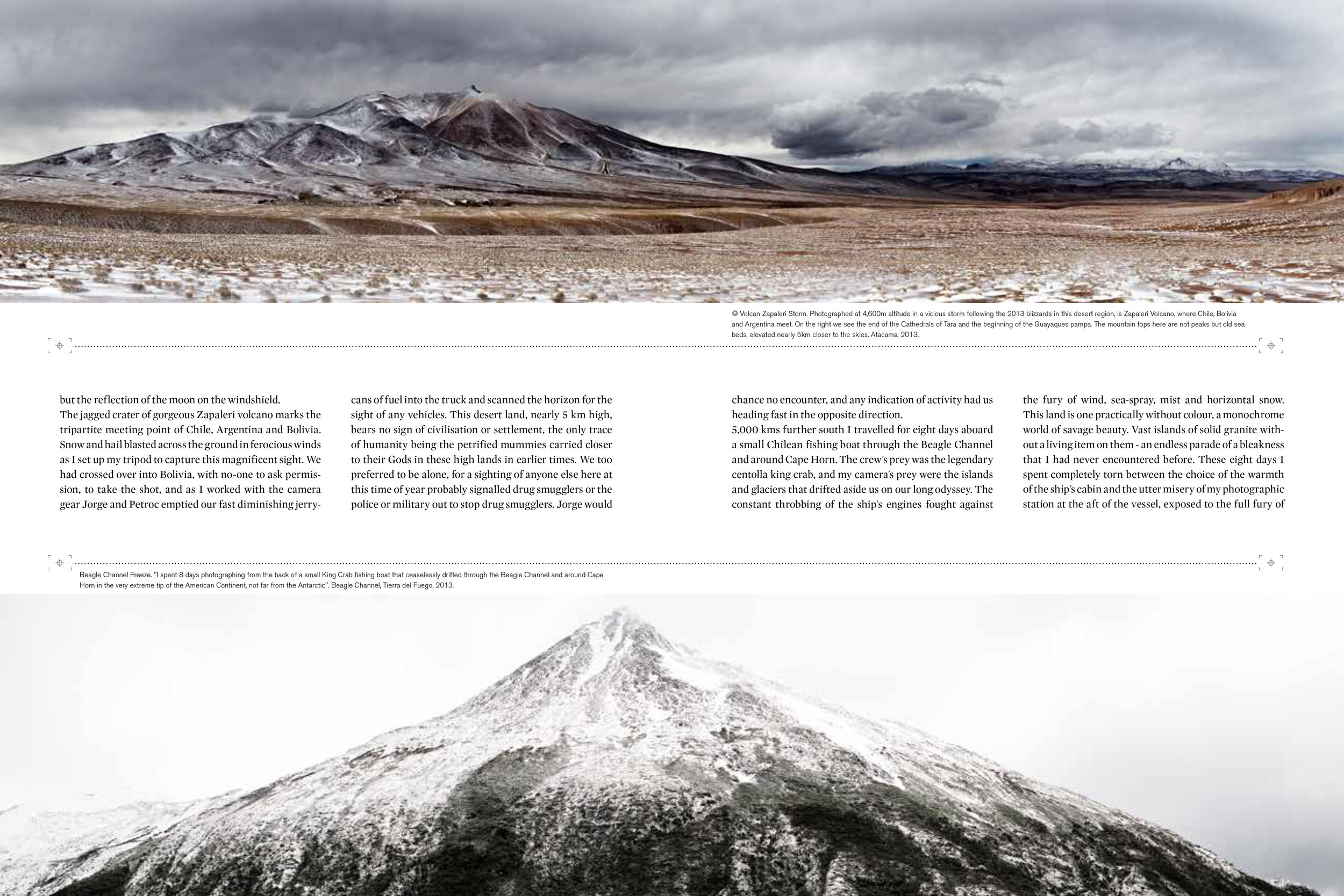

That fugitive sensation is powerfully articulated in Lindsay’s new work. ALTITUDE comprises a series of gigantic photographic images of South American landscapes, from the remote, high altitude deserts of Bolivia, Argentina and Chile, to the bleak desolation of the Beagle Channel and Cape Horn in the extreme south. As Lindsay puts it, ‘The detail and scale of the photography is simply monumental. Scale is important to me, in the subject and in the artworks.’

The process of making these images is not straightforward. First, ship a truck and enduro motorcycle, together with one ton of camera, computer, expedition and survival equipment to Valparaiso, Chile. Next, travel over 40,000 kilometres overland in eight months, much of it through the thin air of the Atacama desert with its relentless winds and nighttime -20°c temperatures. Along the way endure the region’s biggest snowfall since 1947, trapped for eight days in a simple stone refugio, or a week shooting through blizzards from the back of a fishing boat off Cape Horn and Tierra del Fuego. Oh, and don’t forget to make the pictures themselves. Lindsay again: ‘The regions ALTITUDE took me to necessitated a ‘survival’ attitude simply by being there… The imaging process is so laboured and intricate that I’m working on gut instinct and am really only seeing what I framed, and why, months later as the completed work emerges from the printer.’

ALTITUDE is a compelling new series and Lindsay has opened up an exciting new chapter in the convergence of art and eye-popping digital technologies. Beyond the documentary genius of Salgado and the hypnotic appeal of Andreas Gursky, Lindsay’s work elicits a new and different response: a sensory immersion, a fresh and vicarious thrill that fuses classical landscape depiction with the best of epic cinematic composition.

THE REALM OF INFINITY

BY ANA INES FIGUEROA

2015

(Ana Ines wrote this wonderful piece for me on the regions that I travelled through in South America)

Altitude, or Puna in the language of the Inca. A high plateau defined as a vast region locked inside the Andes Mountains. The Puna is a closed-in elevated basin, a territory that combines fossilized sea beds with volcanoes, salty lagoons, hot springs and the geometrical patterns that emerge when different salts crystallise over infinite expanses.

The Puna is a desolate land to either love or fear. It tears sensitive souls to pieces, while makes the strong fearless. It is one of those few places on Earth that man has not been able to alter or domesticate. The Puna changes those who venture into it, whereas it remains unscathed, as ever. The high regions remain untamed, being too high, too cold and too hot. Oxygen is scarce. Ultraviolet radiation is extreme. And the invisible wind accelerates when flying over the salt flats, carrying sand and silica that polish volcanic surfaces until they shine.

The lowest regions of the Puna are three and a half kilometres above sea level, a massive desert where night-day temperature differences reach 60° C: +30 ° C at midday and -30 °C at midnight.

Before the Andes existed and dinosaurs still roamed the South American plains, this part of the world was under the ocean, and for millions of years the depression collected layer upon layer of sediments. These settled, compressed, and waited.

Sometime, about 60 million years ago, subduction of the Nazca Plate under the South American landmass began, and as the marine seabed was pushed upwards the ocean water evaporated. Subduction created friction, so volcanoes emerged to release pressure and heat. Some volcanos spat lava while others exploded and clouds of ashes and silica that turned into stone. And since, wind, water and extreme temperatures have worked as a relentless team designing the land, uninterrupted.

The little water there is collects into lagoons that, in truth, are a saturated solution of salts and minerals suspended in thick brines. Evaporation rate is higher than water input, this is a superb process that creates salt flats, salt lakes, Salares and Salinas. Salts grow, mutate and crop up in geometrical patterns only to be subdued by dissolution during summer rains. Then in winter they are reborn just as leaves do after the snowmelt.

The volcanic fissures sprout thermal waters that smell of sulphures and collect in alkaline flat lakes ridden with algae and bacteria that Andean Flamingos – Parinas in Quechua – sieve through their beaks, surviving thus in a mostly uninhabited land.

Three thousand kilometres south of the Puna, subduction of the Nazca plate uplifted, faulted and folded sedimentary and metamorphic rocks that not as high but yes as desolate, windswept and extreme. Patagonia is designed by ice, wind and cold.

The term Patagonia was encrypted into history by the Portuguese sailors that explored the coast in 1520; few survived. It spans from Pacific to Atlantic and its soul and backbone are the Andes’ peaks that cradle two ice fields recognized as the largest remaining contiguous extra polar ice fields in the world.

The massive dance of ice, advancing and retreating glaciers, scraped and shaped the Patagonia landscape. Draped with driftwood, twisted forests, solid ice. Black, blue, turquoise, diaphanous, liquid and solid water. And wind. More seamless wind. Wind pouring colourless out of the realm of infinity.

© Ana Ines Figueroa